The Intellectual in American Public Life

A lecture delivered on April 30, 1984.

Unusual intelligence and great energy, along with ambition and influence, are not enough to define an intellectual.

Thus a brilliant expert or specialist or technician who devises or affects a specific policy is not by definition an intellectual. The honorable responsibility of such people is to provide their various pieces of the puzzle that the intellectual then struggles to put together into a coherent whole. Specialists know more about their chosen piece of the puzzle than the intellectual can ever master. The expert is like the person watching a baseball game through a teenie weenie knothole in the fence. Every now and again she or he sees the third baseman make a play, and concludes that baseball is defined by the batter staying at the plate until he hits a ball to the third baseman. Everything else is unknown, hearsay, or incidental.

But of course everything else is not unknown, hearsay, or incidental. Thus the intellectual is a person who attempts to put all the views from all the knotholes together in order to understand the game and its consequences. Simply put, the intellectual has a different kind of mind, a different perception and perspective, and attempts to fulfill a different function and responsibility in any culture and society.

Two other points follow upon that definition and conception of an intellectual. First: an intellectual can be a conservative (even a reactionary), a liberal, or a radical. But the intellectual must offer a coherent, internally consistent, and integrated conception of how all the aspects of life interact and come together. Second: the intellectual can function in one or more of the six major arenas of public life. She or he can be involved in electoral politics, in the business world, in an advisory or bureaucratic position, in education (religious as well as secular), in what we now call print and broadcast journalism, or simply as a local, regional or national sage whose idiom is largely based on the oral tradition of the wise person. I propose to explore these non-tenuous examples of influence.

Let us begin with business leaders. Whether or not they know it, many academics share one assumption with a majority of their fellow citizens: all business people are narrow-minded folk driven primarily by greed and concerned largely with that vulgar position known today as "the bottom line." There is considerable evidence to support that analysis and conclusion, but academics do not enjoy monopoly on the intellectual life, and the exceptions have been extremely consequential in American history.

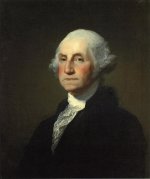

Consider first George Washington. He was an extremely shrewd and successful capitalist who nevertheless developed an integrated conception of American society and its place in the world. It is probably fair to say that George was a slow learner, but the vital point is that he learned. His post-Revolutionary letters and state papers do offer a coherent view of the world. Such an approach would also involve Alexander Hamilton who, if not strictly a capitalist, was surely a well-rewarded entrepreneur as well as a powerful appointed advisor who entertained a ruthless and over-arching conception of the world. His essays in The Federalist Papers, for example, may disturb you but they demand your most serious thought.

We could move on to engage Abigail Adams, who not only managed the family estate with great profitability while John was away much of the time, but who also offered a coherent and critical analysis of the necessary and proper (meaning moral, as well as pragmatic) place of women in a self-defined democratic republic. As with many other American intellectuals, Abigail asked the right questions before they were allowed to become problems.

Which, come to think of it, may be a working definition of an intellectual. Perhaps an intellectual is a person who can see over the horizon.

In any event, let us focus here on three other individuals closer to our own experience: Charles A. Conant, Herbert C. Hoover, and Adolf Berle. At the turn of the century, Conant was a highly successful banker and financial analyst. Boards of directors listened to him with most careful attention. His thought about his experience in the marketplace led him to formulate a general theory of capitalism that concluded with a broad policy prescription based upon the necessity for imperial expansion and a domestic marketplace administered by a coalition of astute corporation leaders and equally sophisticated intellectuals drawn from labor, politics and academia. Conant was in many ways the American precursor of John Maynard Keynes, that would-be saviour of the British Empire, and he exerted a similar kind of influence within and upon the policy-making elite that included Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

For his part, Hoover is still considered by most Americans as the engineer who designed the Great Depression of the 1950s. Oh, my! If only reality was that simple, neat, and smug. Now in truth Hoover was an expert in mining who made millions as a businessman and slowly came to be an intellectual worth our serious attention. Three factors changed Hoover's outlook.

The first was his commitment to the Quaker vision of community. He truly believed that people could and should live together as supportive neighbors and friends. Second, he learned from his experience as a capitalist. Workers should be treated equitably by the corporation; and mindless expansion of the marketplace led to imperialism and war. Furthermore, administrative capitalism subverted freedom and liberty. Third, he concluded that war was the Evil Empire. He thus revised and reintegrated his overview in terms of anti-imperialism, anti-state capitalism, and the integration of culture in terms of local and regional communities. He withdrew American troops from Nicaragua, and refused to send them to Asia. He became a severe and somewhat impatient and cranky critic of centrally managed state capitalism, and flatly told President Harry S. Truman not to embark upon a global crusade against revolutions.

Adolf Berle had at heart a similar kind of contempt for sophisticated trimming, hypocrisy, and hunger for power. He was an unusually successful corporation director who made a fortune from our imperial control of Caribbean sugar and molasses. He knew that world so well that, along with Gardner Means, he wrote a landmark analysis of the nature of the modern corporation that influenced people of at least three generations. Like Hoover, however, Berle had the knack of reading the scribbles on the wall. He saw over the horizon and reported on the prospects, even if he finally chose to try to preserve the status quo.

Berle made his point most forcefully in 1936-37, at a time when the New Deal's version of administrative capitalism had failed to end the Great Depression. He spoke bluntly to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Either America developed a subtle imperial and syndicalist corporate capitalism, or it imagined and created a truly democratic socialism. Roosevelt did not understand the idea of democratic socialism, and if he had would surely have been opposed to the idea. Berle gave over. He first went off to supervise the change of governments in Brazil and ended his career by helping President John Fitzgerald Kennedy plan the imperial fiasco known as The Bay of Pigs. Berle ceased to be an intellectual and settled for being an expert.

Thus it is clear, no matter where you begin, that the intellectual often functions in more than one of my analytical categories. Let us therefore examine three major politicians who were classic intellectuals. Consider first James Madison if only because it really is true that he was the Father of The Constitution. There were a few small groups in America at the end of the Revolutionary War which wanted a strong central government, but it seems clear that most citizens preferred a more decentralized system of power as the best guarantee of democracy and responsive government. Thomas Jefferson was the intellectual and charismatic leader of that majority. Think of it this way: there IS a fundamental difference between the Declaration of Independence and The Constitution.

Madison faced the challenge of devising an analysis and argument that would persuade Jefferson and his followers that empire and centralized power provided the best way to insure democracy and responsive government. With all due respect for experts, specialists, and technicians, that defines a problem of a different order and magnitude. It involved nothing less than subverting the wisdom of the ages.

First in a series of intense but friendly letters, and then in The Federalist Papers numbers 10 and 14, Madison presented a case for democracy as empire. His performance would have earned him PhDs in philosophy, political theory, political economy, history, and the false syllogism at Trinity College, Cambridge. Jefferson surrendered; "I am persuaded no constitution was ever before as well calculated as ours for extensive empire and self-government." Small wonder that he took Louisiana and denied self-government to the citizens of New Orleans. Madison's influence was not tenuous.

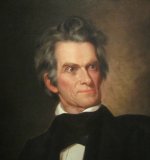

Others disagreed, have indeed continued to disagree down unto our own time. But let us content ourselves with confronting John Caldwell Calhoun of South Carolina. Calhoun was graced with a mind that could challenge Madison - or any other leader of his or our time. We can all agree that chattel slavery did not provide the best ground upon which to stand and fight. But if you read Calhoun carefully, you come to realize that slavery was secondary to his primary concern.

Calhoun challenged Madison (as well as Abraham Lincoln) with the proposition that imperial democracy is a contradiction in terms. Thus, for example, he opposed the war that chewed off the northern half of Mexico. Calhoun argued that democracy, more particularly republican self-government, meant nothing - was indeed a gross hypocrisy - if people could not go to hell in their own way.

I know it may sound strange, but Calhoun was in truth arguing the Declaration of Independence (the right to dissolve one government and form another) against the immutability of Madison's and Lincoln's Constitution. And it is more than just fascinating that John Quincy Adams agreed with Calhoun: Adams had the visceral, intellectual, and moral courage to confront the fundamental issue. Adams argued with great passion that the free states should secede. First.

Those intellectuals did not hold a tenuous position in American life. As Henry Adams later noted, we killed and maimed one million of our own over those ideas. That is hardly to be described as a lack of influence. Or as a tenuous connection with public life.

As it happens, Henry Adams offers a fine example of the intellectual as educator. We might usefully first consider Jonathan Edwards, however, a preacher and a tutor at Yale University who later went to the frontier to live with the Indians and finally became president of Princeton University. In every phase of his life, Edwards offered a powerful and highly integrated overview of the world that exercised enormous influence on American thought and action. One can agree or disagree with the particular explanation of reality offered by Edwards, but one must confront his basic propositions: experience becomes unified only when coherently conceived; and only in the perception of what things go unavoidably and fatally together has suffering any dignity or experience any harvest.

So also with Henry Adams, Frederick Jackson Turner, Charles Austin Beard and Thorstein Veblen; four later intellectuals who moved between formal educational institutions and the broader public arena. Adams, for example, was active in politics and ultimately became a close advisor to John Hay during the period when American foreign policy turned away from continental expansion toward overseas imperialism. Along the way he taught at Harvard, wrote novels, and offered one of the most challenging accounts of American History between 1800 and 1812. And his report on his own Education remains an unnerving account of what happened to the original dream of America.

Turner's famous Frontier Thesis, first offered orally to the public during the great Chicago World's Fair of 1893, deeply affected the average citizen's understanding of this country. He argued that there was a causal relationship between our expansion and our prosperity and democracy. That explanation of American history seeped into grade and high school education, as well as guiding the work of most historians and other academics for at least two generations.

Turner also exerted a direct and highly consequential influence on Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

It is often forgotten that Beard was a highly successful businessman and a life-long activist in politics. His working partnership with his wife, Mary Ritter (who on her own wrote a pioneering study of women in America), produced a long list of books that informed the way that millions of citizens thought about America and its leaders. Again, as with Edwards, one can agree or disagree with Beard, but there is no way to deny the power of his analysis or influence.

While Veblen was more usually associated with universities, his books and essays were also read by enormous numbers of people outside the classroom. The Theory of the Leisure Class foresaw the coming of the consumer culture, and his later works argued with considerable power that capitalism might be managed better by engineers than by politicians. There was a cutting and even prophetic paradox in Veblen, the grand theorist of capitalism, suggesting that in the end the specialist might do better than the generalist.

In some respects, Veblen became a very sophisticated Journalist who offered overarching explanations of reality and policy. He can usefully be considered as one who honed the best of the intellectual tradition inherent in the Muckrakers who played such an important role in the rise of the Progressive Movement. Charlotte Gilman performed a similar role in creating the intellectual capital for what is today called the Women's Liberation Movement. Her first two books, Women and Economics and The Home, were not best sellers; but they did exercise vast and increasing power over the thinking and actions of subsequent generations of American women.

If one were asked, however, to name the classic modern prototype of the intellectual as journalist, the only answer would be Walter Lippmann. He co-founded The New Republic magazine, wrote more than 2,000 editorials for the New York World, and his column in the New York Herald Tribune was read by an estimated 36 million people. Along the way he wrote 26 books and advised an unknown number of elected politicians in the House and Senate, various appointed bureaucrats, and several presidents. Lippmann was anything but tenuous.

In his later years, Lippmann also became something of an oral sage - or wise man - on television. That tradition goes back at least to Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards and was sustained by John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln. It was moved into the 20th century through such Populist leaders as Mary Lease and "Sockless" Jerry Simpson and then revitalized by Mother Jones and Eugene Debs. Debs was as much - and probably more - a moral philosopher as he was a Marxist political economist. And, despite his thin high voice, he could and did change people's minds with his vision of a different and better industrial America.

It would be neat and convenient to argue that Franklin Delano Roosevelt continued that tradition of oral intellectuals. But I am sure that we all know that F.D.R. was not an intellectual. It is possible to argue that Martin Luther King, Jr. was in the process of becoming an intellectual when he was murdered. But with all due respect I would suggest that Roosevelt and King were living on the intellectual capital created by their predecessors. And the truth of it is that despite the great opportunities offered to oral intellectuals by broadcast journalism, there are no great names to identify and discuss.

That unhappy reality takes me back to Veblen and Turner. Their history suggests three propositions. First: the intellectual has not suffered a tenuous position in American public life until the recent past. Second: the intellectual in America may have become a footnote to the ancient wisdom that nothing fails like success. Third: the only way for the contemporary intellectual to regain influence is to imagine a different and better America.

I suggest to you that I have established the first thesis. American intellectuals have exercised great influence in our history.

I choose Turner to illustrate my point about the failure of success. Turner's Frontier Thesis persuaded his contemporaries and successors that America's welfare and democracy depended upon endless growth. Hence the only actionable issue involved how to sustain such growth. That closed off any serious discussion of the character and costs and limits of growth. People who challenged the Frontier Thesis were automatically defeatist if not Un-American.

Finally, I go back to Veblen because in the end he gave over to the experts, the specialists, and the technicians. He was the father of the movement known originally as Technocracy, which does indeed define our present moral, intellectual, and political life. Worse. It limits our imagination and our aspirations and our ambitions. We address our moral priorities and our brains to colonies in space for an elite rather than to ending starvation for the great majority of humankind.

Veblen wrote two books in two years back in 1918 and 1919. The first was called The Higher Learning in America; the second, The Vested Interests and the State of the Industrial Arts. I reread them as part of my research and thought to prepare this paper. I remember reading them first as a graduate student. Then I read them again when I was advising a PhD thesis on Veblen and American foreign policy. It was grim stuff both times. Veblen gives you hardcore analysis of American society. So it was grim the third time.

One could argue, with some considerable persuasion, that Veblen turned to the engineers simply because he concluded that Turner was right: Americans defined better as more and could not be dissuaded from that false syllogism, and hence the engineers were the inevitable rulers.

Now I was trained for five years to be an engineer. But in my good fortune I was also educated to think about tomorrow as something much more than a linear projection of today. I was taught literature, philosophy, political theory, history - heaven knows, even music.

So I suggest to you that if the intellectual suffers a tenuous position in American life in 1984 - it is because the intellectual has ceased to be an intellectual. If you teach a child or a young adult that the primary purpose of education is to get a job, rather than to make his or her own sense of the world, then you will produce a society of robots. The truly frightening aspect of George Orwell's 1984 is that everyone is content to do their job rather than ask the difficult and naughty questions. And take the consequences.

When you come right down on it, that is my definition of an intellectual - a person who asks the difficult and naughty questions so that we may together devise creative answers.

Table of Contents

- The Politics of Ecological Balance

- Seven Americas on the Way to the Future: An Exploration of American History

- The Crisis of American Democracy

- The Legacy of Karl Marx: Or, the Inheritance We Dare Not Squander

- The Intellectual in American Public Life

- Commencement Address

- Fred Harvey Harrington: Committed, Tough and Foxy Educator and Liberal.

- The Intellectual Menopause and Changing One's Major

- The Comparative Uses of Power: China on the African Rim and the United States on the Pacific Rim

- Harvey Goldberg and The Virtue of History

- Vietnam and the Revival of An Anti-Imperial Mood and Movement In the United States and the Beginnings of a Thaw in The Cold War.

- America As a Weary and Nostalgic Culture

- The Potential of Higher Education