Beginning in the 1100s CE, as literacy rates rose among European nobility, the demand for the reproduction of manuscript texts for personal use increased dramatically. Monks had traditionally produced texts in small quantities for use within their own religious communities. As one of the few groups with the education to produce manuscripts on a commercial level, some orders began accepting contracts from private citizens. This proved to be a lucrative profession and formed part of the financial basis for many monasteries in Europe.1

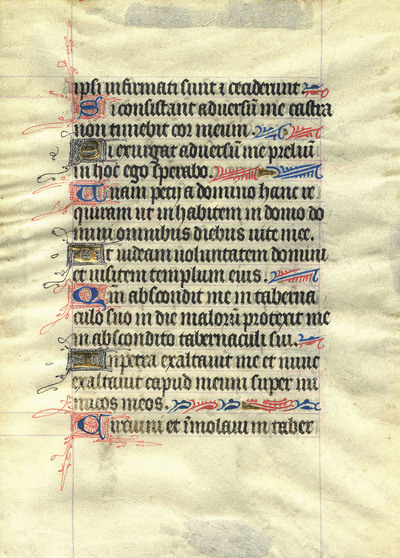

Manuscripts were notoriously tedious to create and a single text could, in some cases, take a year or more for a scribe to complete. By the 1400s, demand for manuscripts had far exceeded what could be produced within the monastic system. Seeing an opportunity for profit, entrepreneurs across Europe began opening scriptoria, workshops dedicated entirely to the reproduction of manuscripts.2 Some scriptories even included craftsmen to produce decorative elements including illustrations and embellished initials or drop caps. These scriptorias served as the predecessors to the publishing houses that would populate Europe after the advent of Johann Gutenberg's printing press.

Notes

- Febvre, Lucien & Martin, Henri-Jean. The Coming of the Book (London, England: NLB, 1976), 18-19. Return to text ↑

- de Heml, Christopher. Scribes and Illuminators (Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 5. Return to text ↑

Leaf from an unidentified missal featuring the traditional red, blue, and gold embellishments. More images here