In direct response to the Szilárd-Einstein letter, President Roosevelt issued a secret order to create a committee to advise top policymakers on the ramifications of atomic research.1 He appointed Lyman J. Briggs, the director of the National Bureau of Standards, to lead the group. The Briggs Advisory Committee on Uranium met for the first time in October 1939. It was equipped with a $6,000 budget and instructions to oversee initial experiments into nuclear fission. After a brief survey of candidates, the committee chose to fund Enrico Fermi and Leó Szilárd’s work on neutron activity.

Nuclear research was also being noticed in the United Kingdom. By March 1940 Birmingham researchers Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls had worked out a series of calculations that suggested that a "super-bomb" was feasible. The duo drafted a memorandum that explained the mechanism by which such a bomb might function and offered an estimate as to the critical mass necessary for effective detonation. They then delivered the memorandum to Marcus Oliphant, a leading scientist at Birmingham. Oliphant in turn passed their findings on to Henry Tizard, chairman of the Aeronautical Research Committee.

Tizard was impressed by the Frisch-Peierls findings and recommended that a small committee of British physicists be convened to discuss the possibility of a super-bomb. Tizard and Oliphant called together James Chadwick, P.B. Moon, Patrick Blackett, John Douglas Cockroft and, at the committee's head, G.P. Thomson. This group famously became known as the MAUD Committee. Though much of the committee was skeptical of a super-bomb, Frisch and Peierls provided strong experimental evidence. Chadwick, in particular, was impressed by the Birmingham scientists' calculations and stated that his own work with fast-neutron fission supported their findings. The committee ultimately recommended an extended study of a possible super-bomb.2

While the MAUD Committee launched into action, back stateside the Briggs Committee floundered. The American nuclear war effort was limited by several factors, not least of which were the reservations held by the National Defense Research Committee’s (NDRC) top scientists and administrators. Vannevar Bush and James Conant, among others, were largely unconvinced by the reports received from their British counterparts.3 To them, the super-bomb was a vacuum sucking up manpower, money, and precious materials. Further complicating matters was the fact that Lyman Briggs intentionally kept the research pace slow and even prevented his fellow committee members from accessing the MAUD reports.

Frustrated by the lack of progress being made by American researchers, Mark Oliphant travelled to the U.S. to meet with the Briggs Committee and other top administrators in the NDRC. He expressed his concerns regarding Briggs' performance and, in July 1941, Vannevar Bush began to restructure the nuclear research program. Bush dissolved the Briggs Advisory Committee and replaced it with the S-1 Uranium Committee under the control of Arthur Compton and the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), a powerful successor to the NDRC.

Notes

- 0446. Szilard, Leo. His Version of the Facts. Selected Recollections and Correspondence. Ed. by Spencer R. Weart and Gertrud Weiss Szilard. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1978. QC16.S95 A254 1978. Return to text ↑

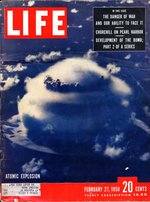

- 0303. "The Atomic Bomb: How the Weapon that Launched a New Age Was Produced; Here is what Americans Can and Must Know About It." Life, Vol. 28, No. 9, pp. 90-100. New York: Time, Inc., February 27, 1950. Return to text ↑

- 0311. Bush, Vannevar. Pieces of the Action. New York: William Morrow. 1970. Q127.U6 B87. Return to text ↑