The Crisis of American Democracy

The Seventh Samuel F. Salkin Memorial Lecture, First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis, October 7, 1982. Published here by permission of the First Unitarian Society.

The contemporary crisis of democracy in America provides the ultimate proof of classic capitalist theory and practice. Failure has finally trickled down from those on high to all of us here below. We at the bottom are not doing significantly more than those at the top to create a healthy, equitable, and humane community. Our rulers are obsessed by the Russians, computers, and robots. We below are immobilized by our fear to make our own history.

Thus the real crisis of American democracy is that there is no crisis.

There is no confrontation worthy of being compared with the fight over the Constitution, with the anti-slavery movement, with the battles of the Populists and Progressives, with the militance of the working classes during the 1930s, or even with the inclusive visceral anger of the black civil rights agitation. The best that we can see today involves various special interest groups trying to improve their position within a generally oppressive system of corporate-statist capitalism. They are useful and perhaps even noble battles, but they do not deal with the central issue of imagining and creating a truly democratic social order.

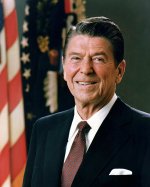

This is nicely illustrated by the limits of our response to President Ronald Reagan's gross misuse of a dramatic quotation from one of our illustrious forefathers. As you may remember, Reagan organized one of his major speeches (and much of his 1980 campaign) around Thomas Paine's euphoric revelation in 1776 that "We have it in our power to begin the world again." Those words do indeed tilt one's brain, tingle one's spine, and spin one's soul. And it is possible to develop a challenging if ultimately unpersuasive argument that our Revolutionary and Constitutional forefathers did make a valiant effort to change the strategic or basic nature of the social contract as it then existed in Western Civilization.

I will return to that point, but for the moment let us concentrate on Reagan's use of Paine's quotation. The President clearly does not understand what it means to begin the world again in our time. Short of having the Lord on hold on the Hot Line, the only way we Americans can begin the world over again in the 1980s is either to wage an all-out nuclear war or to undertake and carry through structural changes in the fundamental social, political, economic and power relationships in our society.

Reagan does not want such changes. But neither does he want such a war. He seeks instead to use more bombs to create a Fortress American Empire that will restore a romantically distorted idea of free enterprise capitalism. He is truly so naive and so ignorant as to honestly believe that corporations are individuals with social consciences: citizens concerned to, and capable of, recreating a free marketplace political economy in which the poor are cared for by the rich until such time as the wealthy create jobs instead of providing charity.

It is all responsible, noble and caring in the way that John D. Rockefeller handing out dimes on the street corner was responsible, noble and caring. Of course it is a joke. Of course it is scary. Of course it is arrogant. Of course it is morally irresponsible. And of course it will not work. It does not work.

But we critics are not doing much better. We are good critics. On balance even excellent critics. We have examined the system and found it wanting: defined it once and for all as a system that does not honor its own principles or realize its promises.

Beyond that, we have mustered our will to stop an immoral war, and to challenge the idea and the practice of a Fortress American Empire. We struggle to improve the life of women, blacks and other minorities, and to secure the dignity of the old and the infirm. There is no reason for us to apologize.

But we have not created a crisis about the character or legitimacy of the existing American system. Until and unless we create such a crisis there is no possibility of beginning the world again. Thomas Paine came in at the end of the game. All the hard and dangerous work had been done: the people were in the streets, and the new vision was in their mind.

We have been in the street, but we have offered no new vision of America. We have not imagined, and then explored and developed, let alone agitated, a different conception of America. And so we find ourselves confronted with various distorted impressions of the past.

There are no easy answers, but I would like to offer the paradoxical suggestion that we can begin by giving serious thought to the ideas of some great American conservatives. I realize that this is most unorthodox - terribly un-Leftish. The conventional wisdom of the Left can be summarized this way: if it is conservative, then it is bad or irrelevant - if not probably both and even worse.

Such irrationality is comprehensible once you realize that the Left has lost, or at any rate mislaid, its power of discriminating between a John Quincy Adams and a Ronald Reagan, or between a Henry Adams and a Samuel Huntington, or between a George Frost Kennan and a Henry Kissinger. Perhaps it is all understandable, but it is nevertheless terribly dangerous.

Let us begin with Reagan. He proposes a New Federalism that denies elementary social responsibility and gives corporations more power. And he clutches power by controlling the budget. I prefer John Quincy Adams. He proposed that the non-slave-holding states secede from the Union in order to create a more nearly perfect social contract. A more human community. "The bargain between freedom and slavery," he asserted as early as 1820, "is morally and politically vicious." It robs "the poor, the unfortunate, the helpless" of their elementary rights. Secession in the cause of freedom would be traumatic, demanding, and dangerous; but "I dare not say that it is not to be desired."

There is tough talk not heard today on the Left.

Next consider a modern product of Harvard. Professor Samuel Huntington defines the crisis of democracy in terms of large numbers of citizens refusing to acquiesce in government by "a relatively small number of Wall Street lawyers and bankers." If only Huntington was correct! His "large numbers" are as much a figment of his imagination as the tender loving care of his lawyers and bankers. Truth to tell, most of us may bitch about lawyers and Wall Street bankers but we go right on sitting on our thumbs. But it is important to understand that he thinks that substantive, tough criticism is "excess democracy." Hence he argues that the President should be freed from all "picayune...restrictions and prohibitions." It follows that the "right and ability to withhold information" is essential.

How refreshing it is to turn to a grandchild of John Quincy Adams. Henry Adams observed that such attempts to impose uniformity upon a continent might easily - if not certainly - produce more corruption and other evils than the wickedness commonly ascribed to diversity. He concluded his evaluation with this judgment: the old system had collapsed, and the refusal to imagine and create a new social compact meant that "nine-tenths of men's political energies must henceforth be wasted on expedients to piece out - to patch or, in vulgar language, to tinker - the political machine as often as it broke down." And it surely has been breaking down.

Very few leaders within the memory of any of us now alive have confronted or echoed either John Quincy or Henry Adams. Either we change the system or we idle away our time and lives inventing new variations on the old excuses for the failures of the existing system.

If we are to confront and begin to deal with that challenge, then we can do much worse than to consider the moral of the delightful story told by Henry about his grandfather John Quincy. One day Henry did not want to go to school. He sulked in his room, puttering around with this, that, and the other. His mother failed to budge him. Henry stayed in his room. John Quincy went upstairs, said not a word, took Henry by the hand, and walked him silently down the road into the school house and into his seat.

I think that it is time that we took ourselves by the conscience and walked ourselves down the road to a discussion of changing the system.

No matter where or under what circumstances I offer that suggestion, I am always asked to be specific. Here are sample questions. "Could you please give an example;" "Please be specific;" "Where do we start;" "What do you suggest;" "What precisely do you propose;" "Isn't reform safer;" "What about guaranteeing basic rights;" "Won't such changes hurt many people;" and "Doesn't what you suggest threaten our military security." That list is not exhaustive, but it is representative. The basic answer is that we critics of the existing order do not have a neat computer printout satisfying everybody. We never will have. Our principle is that we will devise our work-a-day efforts together in the course of a tough democratic dialogue.

Speaking for myself, therefore, I do not think that I should be expected to offer a neat blueprint for transforming America into an ideal community. I accept the responsibility for asking relevant questions, and to offer my thoughts about alternatives; but it is our mutual obligation to devise the answers and muster our will to act in ways that will translate those answers into a different and better America.

In order to do that, we must first understand why in recent years the Left has generally failed to evoke a broad and sustained response from other Americans. Only then can we consider specifics.

For all the talk about change being the central characteristic of American history, our culture has displayed a remarkable fidelity to certain assumptions and axioms of political philosophy or theory. Most of those were born of our early experience as a group of interrelated but nevertheless separate and different colonies ruled by an increasingly powerful and arbitrary metropolis. Thus in many respects, and not at all surprisingly, the cornerstone of the evolving American outlook was the principle of liberating society from domination by the State. The citizenry, individually or in various largely voluntary associations, was held to be superior to the State.

From that premise flowed two corollaries: action by the State should be limited by basic organic law and also in terms of subject matter; and only citizens of Virtue - defined most explicitly by John Adams as "a positive passion for the public good" - should be trusted with State power. Such a conception of virtue may bring a smile to our souls in 1983, but it has been a powerful force in American culture.

During the next two generations, say from the 1890s through the 1940s, the corporation came to replace individuals and voluntary associations as the elementary units of society. Some elements in the New Deal coalition of reformers and managers fought a rear guard action against that process. So did Herbert Clark Hoover and a small band of sophisticated traditional conservatives. But they lost, and the corporation came to dominate society - the body politic.

Newspaper clipping depicting four types of government. (Extract from Williams's high school scrapbook, ca. 1930s.)

Willy-nilly, therefore, the citizen turned to the State to control the corporation. The definition of Virtue underwent a subtle and devolutionary change: from being "a positive passion for the public good," it became an ability to manage a centralized system and hopefully provide a minimal degree of equity in a global empire. As a result, the legislature, that classic instrument of society to assert and maintain its primacy over the State, became increasingly an instrument of the State. And, during the process, freedom and liberty were steadily displaced from human labor and public affairs into the secondary arenas of consumption and leisure.

The result is a paradox. With the decline of Virtue, a decreasing number of citizens consider it worthwhile to vote. At the same time, various groups within the system struggle to reassert, at least on limited and special issues, the principle of society controlling the State. And through all of this process the Left has largely failed to comprehend why its proposals to provide better and more humane leadership of the State have failed to attract consequential or sustained support among the citizens.

Now it is true that the American Left has suffered from being identified with the monstrous distortions of the socialist ideal that have taken place in the Soviet Union, China, and elsewhere. It shares the blame for that situation with its irresponsible, vicious, and even evil critics. But the fundamental problem is that the American Left since Debs has failed to come forward with an alternate conception and model of socialism that honors the fundamental principles and axioms of American political philosophy as I have outlined them earlier in these remarks. The traditional American Left version of State Socialism appeals to me no more than it does to my neighbors who are loggers, truckers, longshoremen, secretaries, mill hands, and small businesspeople. They seek somehow to reassert the primacy of the individual and voluntary associations - the citizenry, the society - over the State.

So we are back with John Quincy and Henry Adams - and Debs. There is no consequential segment of the Left agitating a modern version of John Quincy's call for the free states to secede from slavery and create a more perfect Union. We prefer to concentrate on contemporary proposals to do what Henry called tinkering with a system in which corporations and the State dominate society.

Once again, that is why the crisis of American democracy is that there is no crisis.

It is only fair, as I come to deal with those questions I am always asked, to acknowledge that citizens on the Left have several of their own. Some of them are the same as those asked by liberals and conservatives. Allow me first, therefore, to confront four of those doubts which arise from the implied or explicit decentralization that I advocate.

First: won't your proposals weaken or even lose certain basic rights and programs that are part of the American political and social philosophy? No. I am not proposing the fragmentation of America into some magic number of wholly independent nation states. Such an idea is so inane that I am constantly dumbfounded that otherwise intelligent people fret about it as a realistic possibility. The fundamental guarantees of American freedom and liberty, beginning with the First Ten Amendments, would be guaranteed and even extended. The object is to provide all citizens with a greater opportunity to exercise those rights according to their own ideas and preferences.

Second: won't your proposals involve a period of transition that will subject some or many people to economic and psychological difficulties? Yes, but hear me out. I am not going to base my reply on the all-too-evident truth that the existing system has for many years subjected millions of people (elsewhere in the world as well as in America) to such deprivation and pain. Not even on the probability that the continuation of the present order will increase those costs.

Nobody has yet devised a way to transform a society without causing varying degrees of pragmatic trouble and heartbreak. It may be one of our more arrogant and irresponsible American conceits to think that we have discovered the free lunch. But surely we can muster the will to face the truth that our historical achievements - and they are many and real - were paid for by slavery, the destruction of Indian culture, wars of imperial expansion, and even one million dead and maimed in our own family bloodbath.

Hence the real issues buried in this question involve how to keep the costs as low as possible; how to make them meaningful to the human beings who pay them; and how to honor and redeem those costs by creating a better America.

Three: won't your proposals risk the national security of the United States during the era of transition? Possibly, but I consider it highly improbable. I say that not primarily because we could hardly be at higher risk than we are today, but because defining America as more important than Russia would enable us to straighten out our strategic priorities.

Ever since 1945-1946, American leaders have largely defined foreign policy in terms of confronting and transforming the Soviet Union. This created an Alice-in-Wonderland situation which combined the worst of isolationism and internationalism and produced the craziest of all possible worlds: a Fortress American Empire.

We must return to that eerie warning voiced by John Quincy Adams on July 4, 1821: "America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.... She might become the dictatress of the world; she would no longer be the ruler of her own spirit." Surely you are aware that we are in mortal danger of losing our soul. Hence I say to you that I choose to risk losing my life to save our soul rather than to be sure of losing my life trying to save an immoral empire.

Four: do you really think that the corporations and the centralized federal State can be brought to bay and ultimately tamed or transformed by local, state, and regional associations of citizens? I don't know, but it's the only worthwhile game in town, and I have chalked my cue and am ready to play. That brings us to some of the other questions about specifics.

All answers become inconsequential indulgences without a commitment to changing the existing system. If you are content to continue tinkering, then most of what I have to suggest becomes irrelevant. By commitment I mean serious and sustained intellectual, moral, and political labor designed to persuade other citizens that it is possible to build a better America. It means trying to be an old-fashioned Virtuous citizen - defined by "a positive passion for the public good." If you feel that desire stirring in your life, then I offer two specific suggestions.

The tax system is the heart of any State. Whatever their many strange, and sometimes frightening, distortions and misapplications of the basic American political philosophy that I have defined, contemporary conservatives and reactionaries understand and act upon that fundamental truth.

We who seek to change and improve America must do no less. That is where our revolutionary forefathers began - "no taxation without representation" - and that is where we must begin again. The tax aspect of the crisis of democracy bears directly on every issue of consequence. There is no mystery about this: the contemporary assignment and allocation of taxes is inequitable, undemocratic, wasteful, and disingenuous. No one should be surprised that many individuals and groups concentrate their energies on protecting their narrow interests rather than promoting a balanced, morally responsible conception of the general welfare funded by taxes.

Here the Constitution offers the Left a fulcrum. That document empowers the federal government - the State - but also other duly constituted public institutions to levy and collect and disburse various tax monies. The sacred text does not say, however, that the federal government has exclusive power either to access, collect, or allocate such funds. It merely says, Article I, Section 8, that the Congress "shall have" such power. The phrase "shall have" is fundamentally different than, say, the words "must" or "exclusively;" or the phrase "is solely charged with the responsibility for."

Thus it is wholly constitutional for a political movement seriously concerned with democracy and the decentralization of power to create a tax structure that mandates local communities, states, and even regional associations of states, to collect and allocate 65 or 70 percent of all tax income. The purpose would be to make the State dependent upon and an instrument of the citizenry. We can, if we choose to do so, decide how much we will spend on social justice, public works, education, and defense.

I have sometimes suggested that a relatively small number of citizens (say 20 percent) could force the State to change the existing system of collecting and allocating taxes. That could be accomplished by mounting a sustained refusal to pay taxes as a protest against the arbitrary inequities of the tax system and the elitist misallocation of such monies. Twenty percent of the adult population charged with willful disobedience of the tax laws would flood the courts, the jails, and the welfare system. Such action would make a joke of the State. It would be the American equivalent of a general strike.

Critics sometimes ask me why it would not be more effective and responsible to establish tax clinics to teach the poor and lower income groups how legally to lower or even evade taxes. I have no wrangle with that proposal as a better than average way to tinker with the system. But that is all it is: a way to tinker with the system. It grossly underestimates the intelligence and ruthlessness of the State. The Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Bureau of Investigation would pluck you off one by one while the minions of the State changed the law. Having been harassed by both institutions for more than 20 years, I prefer to be part of a broader and more visceral confrontation with the State.

So finally - to the basic question. However it is asked, it always comes down to this: how do we go beyond saying NO? Saying NO is terribly important; indeed the cornerstone of what our forefathers called Virtue, but it is only a beginning. We must imagine a different life and culture.

First of all, I think that involves reasserting the supremacy of the legislature as an instrument of the citizenry in order to destroy the legislature as a tool of the State. Second, it hinges upon our creation of alternatives to the corporation.

If we are to so transform - or revive - the legislature, we must devise and agitate a concrete program supported by a strong plurality of citizens dedicated to changing the existing system. The guts of it all have to do with the allocation of taxes and the positive assertion of elementary human rights. Either you subsidize corporations or you do not. Either you build redundant nuclear weapons and delivery systems or you do not. Either you help the poor and other disadvantaged to become full citizens or you do not.

No one can make those decisions in a responsible way unless they have come to terms with the kind of America they want to create. If you want to tinker with the system, somehow hoping to save it or at least postpone its collapse, then you jiggle the collection and allocation of taxes in an effort to keep all the balls in the air. If you want to build a different and better system, then you allow some of those balls to drop to the ground.

I want to change the system. I could not care less about the corporations and the Pentagon. We can create a different economic system, and we have enough bombs to insure our security while we revive Virtue - that "positive passion for the common good."

I want to invent a new way for individuals and groups of citizens to use modern technology to practice freedom and liberty in association with each other. I am sympathetic to the idea of local and regional public enterprises. It is not so much that small is good, as that small is human. I am willing to tolerate a significant degree of inefficiency in order to allow people to make their own mistakes, to practice democracy on the job, and to create an educational system that informs people that they can learn as much from reading Shakespeare and William Blake as from becoming a master slave of Apple, Texas Instruments, or IBM. Or a pawn of the State immunized to freedom and liberty by the placebo of world power.

In short, I have chalked my cue, and I have come to play the only game in town. I want to transform the crisis of democracy into a true crisis.

Table of Contents

- The Politics of Ecological Balance

- Seven Americas on the Way to the Future: An Exploration of American History

- The Crisis of American Democracy

- The Legacy of Karl Marx: Or, the Inheritance We Dare Not Squander

- The Intellectual in American Public Life

- Commencement Address

- Fred Harvey Harrington: Committed, Tough and Foxy Educator and Liberal.

- The Intellectual Menopause and Changing One's Major

- The Comparative Uses of Power: China on the African Rim and the United States on the Pacific Rim

- Harvey Goldberg and The Virtue of History

- Vietnam and the Revival of An Anti-Imperial Mood and Movement In the United States and the Beginnings of a Thaw in The Cold War.

- America As a Weary and Nostalgic Culture

- The Potential of Higher Education