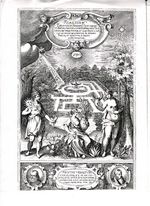

The earliest surviving seed and nursery trade catalogues have historical links to older herbals, books of plants made for the study of medicine and botany. Herbals were produced both to identify plants correctly so as to treat illnesses, and also to classify the many new plants arriving in Europe from the Near East and the Americas. Starting in the late 16th century, it became fashionable for kings and wealthy aristocrats to outdo one another in amassing large collections of exotic plants. To add to the prestige of these collections, some owners had them catalogued in elaborately illustrated books called florilegia. While the classification of plants resembled that of the herbals, the florilegia emphasized plants’ ornamental rather than medicinal value.1

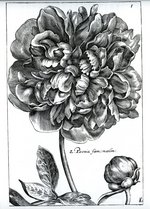

The oldest surviving European plant catalogue is the 1612 Florilegium by Emmanuel Sweerts, a Dutch merchant of bulbs, plants and other novelties from distant lands.2 Produced just over 20 years before the height of Tulipomania, it contains many tulips, as well as other bulbs and herbaceous flowering plants. Rather than being an album of Sweerts’ collection, it was an actual catalogue of plants he could supply for sale.3 A second florilegium, the Hortus Floridus published by Crispijn van de Passe in 1614, was designed as a tool that salesmen could use to show what the plants would look like in bloom.4 Several engravings from these florilegia, which convey the wonder with which 17th c. Europeans regarded exotic flowering plants, are scanned below. In 1621, René Morin of Paris issued the first French printed plant catalogue.5