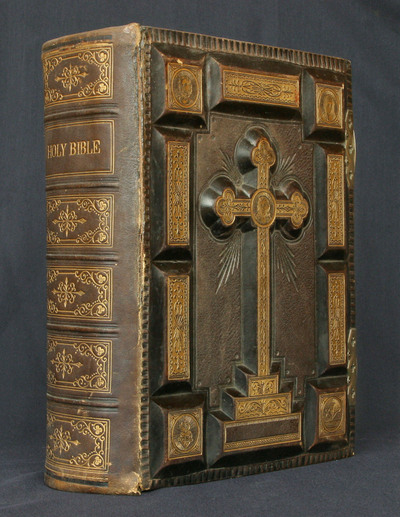

Johannes Gutenberg developed his printing press in a society in which participation in organized religion was nearly unanimous. Given the influence the Church held in Western Europe during that time, it is unsurprising that the first printed book was the Bible and that arguably the most influential printed work of the time was Martin Luther’s The 95 Theses. In fact, a great number of the earliest printed works were of a religious nature.

The clergy quickly adopted the printing press, sometimes replacing their traditional scriptoria with a press. The ability to circulate theological materials among clergymen at a much greater rate was generally seen as desirable. Increasing literacy rates and prevalence of religious texts resulted in a growing subsection of the European public with direct access to religious materials.1 Though the Roman Catholic Church maintained that only members of the clergy were qualified to interpret the Bible, this new degree of access to religious texts provided impetus for a growing reformist movement. With the advent of Luther's Theses, the printing press became central to the Protestant cause and ideology.2 Protestantism encouraged the direct questioning of Papal authority, accused Church officials of abuses of power, and emphasized personal interpretation of Scripture. The ability to distribute religious texts and radical theory to the reading public allowed for a fundamental shift in the relationship between parishioners and religious officials.

The conflict between Protestants and Catholics was an open one with both sides seeking the support of the public. The printing press became an important weapon in the Reformation. Both the Protestant and Catholic propagandists made use of the printing press as a means of influencing the public. Protestants used the printing press to proliferate revolutionary theological material at a popular level, while the Catholic Church produced large quantities of anti-Reformation texts.

Ultimately, the Reformation resulted in a long series of conflicts--both ideological and violent--that continued until the mid-17th century. The printing press played a significant role in communicating the ideas that fuelled this theological war and was responsible, in part, for the Reformation’s effect on Western religion and politics.3

It should be noted that Jewish and Islamic groups were traditionally less receptive to the printing press, and generally preferred to produce written religious texts until the 18th or 19th centuries. Most Eastern religion communities also rejected the moveable type press, though more frequently because of the difficulty of casting hundreds or thousands of individual characters. As a result, the earliest printed religious texts are almost exclusively from Christian documents from Europe.

Notes

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 77. Return to text ↑

- Spitz, Lewis W. The Protestant Repformation 1517-1559 (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1984), 68. Return to text ↑

- Spitz, Lewis W. The Protestant Repformation 1517-1559 (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1984), 86-101. Return to text ↑

Saint carrying a girdle book. 1400s. More images here

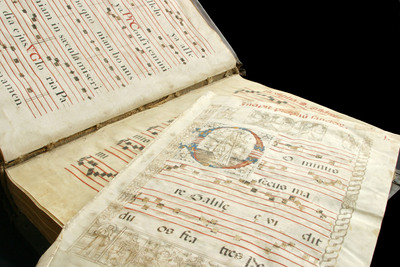

Loose leaf from a Gregorian chant book. 1400s. More images here