“After the age of three score and ten, it is presumed that you live on time borrowed from the devil – who else? But it’s all right. I have been in his debt now for two years and four days, and I guess his time is just as good as any other.”

Roger continued working for Scientific American into the early 1970s, and it wasn’t until 1973 that mention of his difficulty completing projects came up in general correspondence. Letters from the magazine’s Dennis Flanagan were initially supportive of Roger’s difficulties, and he made several accommodations and offered various firm suggestions for improving Roger’s final products. Eventually, however, Flanagan expressed open disappointment with the quality of Roger’s output, and further correspondence with C. L. Stong suggested that Roger would soon discontinue work for the magazine. The main reasons for Roger’s inability to maintain his standards were cataracts in his eyes and the resulting deterioration of his eyesight, which led to an inability to judge where a writing utensil’s tip would meet the paper. Regardless, Roger kept up an active role in the magazine through 1974 and maintained his ties with various Scientific American associates. After the death of C. L. Stong, “The Amateur Scientist’s” longstanding editor, Roger’s old column was disassembled in 1976. Upon later reflection, Roger shared that his work as an illustrator had never been part of any plan, unfolding naturally of its own volition:

“I think my illustrating is the result of an incredible sequence of accidents over which I had very little control. Everything I touched, even in the most altruistic spirit I can think of, has eventually helped pay the rent. And it all started in the spirit of good clean fun.”

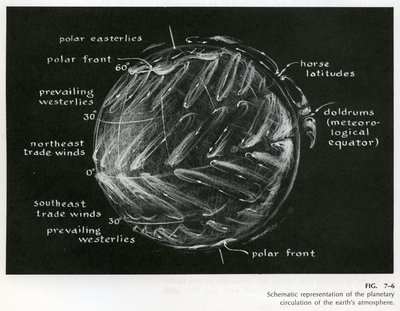

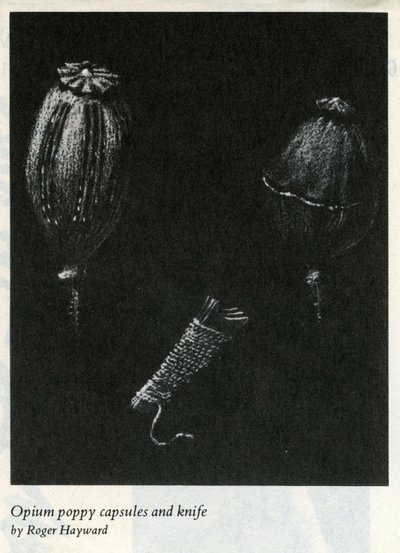

Though his collaboration with Scientific American was coming to an end after twenty-four years, Roger continued to work on other projects that were destined to see print. Perhaps the most significant was the publishing of an oceanography text by Prentice-Hall in 1972, for which Roger was the primary illustrator. The Opium War, for which Roger provided several illustrations, including a rendering of an opium pipe, was finally published in 1975 by University of North Carolina Press, followed by a paperback version the following year. While Roger was mostly finished with composing art himself, he still had much to say about its general practice:

“The one unforgivable sin in art is indecision. If something is wrong it should be completely erased and then redone so the observer can’t tell.”

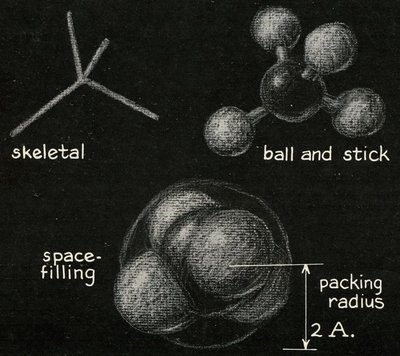

Though Bill Freeman disassociated himself from W. H. Freeman & Co. the previous decade, he collaborated with Roger around this time on several projects through his new publishing organization – Freeman, Cooper & Company. In time Roger provided over fifty illustrations for an organic chemistry text authored by Ruth Walker. The book was mostly unsuccessful, but still sold over a thousand copies, for which Roger was awarded around $124 in royalties. Roger also worked on 3-D and the art of scientific drawing, but the project itself never neared completion, although Roger generally mentioned it to others with great enthusiasm.

Reproduced illustration by Roger Hayward of various methyl molecule models as published in Scientific American, 1973.

Reproduced illustration by Roger Hayward of the planetary circulation of the earth's atmosphere as published in Oceanography: A View of the Earth, by M. Grant Gross, 1972. More images here

Reproduced illustration by Roger Hayward of opium poppy capsules as published in The Opium War, 1840-1842, by Peter Ward Fay, 1975. More images here