While the atomic bomb held terrifying possibilities for the future, it was also an idol for certain the American public to worship. Despite its theoretical conception in Germany, its gestation in Great Britain, and the major contributions to its birth by foreigners like Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller, the bomb seemed uniquely American.1 Born in the wild New Mexico desert out sheer force of will, it embodied the indomitable rogue spirit that romantics assigned to the United States and its people.

Within days of the bomb's appearance on the front page of newspapers, atomic energy had become a symbol of the new America, one that encapsulated strength of mind and industry and promised a bright future. Virtually nothing was popularly known about the particular machinations of the bomb, but few cared. The American people wanted a vision of the future and, if hard facts were not always available, then speculation would suffice.

As a result an entire subgenre of American informational literature appeared virtually overnight. Texts ranging from single-page newspaper articles to full novels emerged, teasing readers with images of atomic comforts. Some authors worked to provide their audiences with a simple, intelligible overview of atomic history, covering the highlights of physics and radiation research from Henry Becquerel's age to the present.2 While informative and accurate, these histories lacked the excitement that the American public craved.

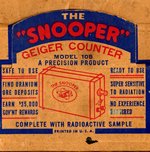

Noting the spending boom of the early post-War era, a few clever writers realized that Americans craved innovation that they could own. Military dominance, as an abstract concept, was good but meant little to the average person.3 Nuclear cars and boats powered by uranium pellets, whole neighborhoods heated by a central power plant, even vacations in space courtesy of nuclear fuel - these were the fantastic prospects that interested the American consumer.4

Notes

- 1167. The United States Delegation to the Fourth International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. Century of the Atom. Washington, D.C.: USAEC, 1971. Return to text ↑

- 1182. Davis, Helen Miles. Atomic Facts. No publisher, circa 1950. QC173 .D38 1950. Return to text ↑

- 1192. Dietz, David. Atomic Science, Bombs and Power.New York: Dodd, Mead, 1954. QC773 .D5 1954. Return to text ↑

- 1175. Cox, Donald & Michael Stoiko. Spacepower: What It Means to You. Philadelphia: Winston, 1958. TL790 .C7 1958. Return to text ↑