Before the late Middle Ages, parchment was the preferred material on which to write. Parchment was made from an animal pelt (traditionally goat, sheep, or calf) that had been soaked in water, bathed in a lye solution to remove all of the hair, stretched, scraped, and dried. After the material had been dried, it was treated to give it a smooth finish capable of retaining ink. Because of its cost, parchment was unsuitable for short-term record keeping and could not be sustainably produced in the quantities necessary for the mass publication of a text. To make matters worse, only the highest quality parchment, called vellum, could be used in a printing press, thereby making the expense of printing with parchment astronomical.1

The printing press would have had little chance of succeeding had parchment been the only material available; the cost of the substrate would have doomed the endeavor. Fortunately, Europeans had been introduced to an alternative material for writing as early as the 12th century CE. Paper had been invented in China in the 2nd century BCE and, through trade with the Islamic merchants, had passed from China into the Middle East and Northern Africa..2 These Middle Eastern traders in turn introduced the fundamentals of papermaking to Italian and Spanish traders who opened paper mills in their home countries and other parts of Europe.

Paper provided a solution to the question of a cost efficient printing substrate. Unlike parchment, it was relatively inexpensive to produce and could be made in much greater quantities. With the proper treatment, paper was able to take impressions well, hold ink, and though not as durable as parchment, could be preserved for long periods of time.

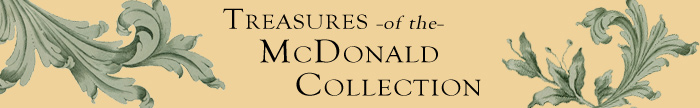

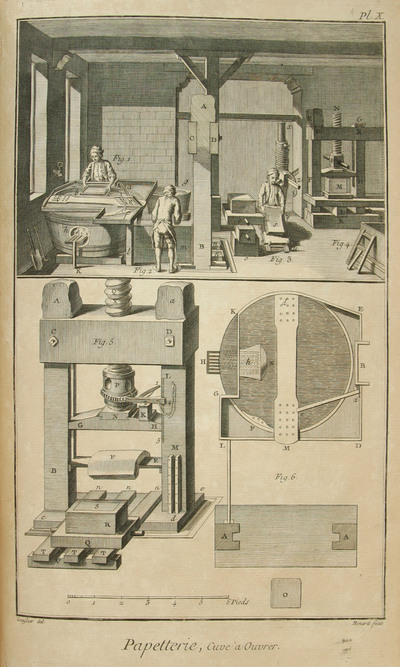

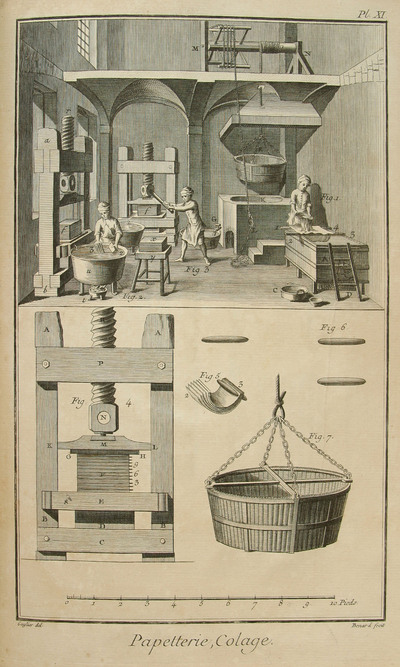

Wood pulp paper, the type of paper we see most frequently today, did not appear until the mid-1800s. Instead, medieval European paper was traditionally made from recycled rags, resulting in the term rag paper. The long and complicated process of papermaking began with specialized dealers responsible for collecting the raw rags. These rags were then sold to papermakers who would begin preparations by cutting them into small pieces and mixing them with water to ferment, a process that caused the cellulose to separate. This material was then milled (traditionally in a converted corn mill), mixed with soap to create a paste, and spread in a form to dry. The paper then went through an extensive wetting, drying, and pressing process before being coated in size and textured.

Paper was an integral part of the printing process and, as printers spread throughout Europe, so did the papermakers, finding their way into France and Germany and eventually Northern Europe. The paper market was competitive and as the number of papermakers increased, so too did the demand on paper's primary ingredient—cloth rags. Some papermakers were forced to hire agents to travel from village to village purchasing rags. Because the demand for paper exceeded the availability of raw materials, there was an almost constant shortage of paper in Europe during the Middle Ages.3

Notes

- Febvre, Lucien & Martin, Henri-Jean. The coming of the Book (London, England: NLB, 1976), 18. Return to text ↑

- Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft (New York, NY: A. A. Knopf, 1947). Return to text ↑

- Febvre, Lucien & Martin, Henri-Jean. The Coming of the Book (London, England: NLB, 1976), 33-44. Return to text ↑

A depiction of the papermaking process from Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie. More images here

A depiction of the papermaking process from Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie. More images here

A depiction of the papermaking process from Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie. More images here