|

Hemoglobin fascinated Pauling throughout his life. He began experimenting with it

in the early 1930s and continued to write about it until his death in 1994. Since

Pauling found hemoglobin intriguing, he learned all he could about it, chemically,

biologically and structurally. The exact structure of hemoglobin was determined in

1959 by Max Perutz of Cambridge University; however, prior to then Pauling knew as

much as anyone about its structure.

In 1935, Pauling chose hemoglobin as one of his first organic substances to investigate.

Several motives elucidate his decision. Hemoglobin is easily obtainable. During this

time, the 1930s and 1940s, no one knew for sure which substance in the human body

controlled heredity, but most scientists believed proteins, such as hemoglobin, held

the secret to life. Proteins are fragile substances to study, and hemoglobin's accessibility

enhanced its allure. Hemoglobin can be studied by x-ray crystallography, a technique

Pauling had learned while working with inorganic compounds as a graduate student.

Also, hemoglobin is a rather large macromolecule, but it can be broken down and analyzed

in sections – which is exactly what Pauling did.

|

|

Click images to enlarge

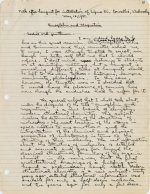

Linus Pauling, in lecture at California Institute of Technology. 1935.

"Hemoglobin and Magnetism." May 12, 1937.

"It [hemoglobin] is a good substance from the standpoint of a chemist, because of

its availability. All you need to do is to catch somebody, introduce a hypodermic

needle and draw out a sample of blood. A standard victim of this practice, weighing

perhaps 120 pounds (it's easier to catch them small!) contains in the red corpuscles

in his blood one and two-tenths pounds of hemoglobin."

|