Dublin Core

Title

Jerry Franklin Retirement Lecture

Description

Jerry Franklin was highly influential as a leader of the Andrews Forest program and in regional, national, and global forestry issues while he was a Forest Service scientist and then as a professor at University of Washington. In this 1991 lecture on the occasion of his retirement from the Pacific Northwest Research Station of the Forest Service, Franklin describes the major accomplishments and lessons learned during his career spanning 34 years to that point. He describes his nine professional lives (i.e., the major themes of research and outreach during his career), but he had to stretch it to eleven areas of major accomplishments.

Franklin begins the lecture by acknowledging people who had major influences on his early career by way of encouragement and example. He then begins recounting his major efforts beginning with subalpine forest ecology, which he found to be an attractive part of the Northwest landscape and little studied. In that period, he learned two lessons: first, if something looks like a good possibility, go for it; second, his objectives were going to evolve, go with it. His second “life” was natural areas, especially Research Natural Areas, and he found that establishment of them could get fraught politically. He describes how this work brought some important opportunities, including engaging young scientists in the program and working closely with Ted Dyrness. His third life was vegetation analysis, which was criticized “not science” and “not truth,” yet working with it led to some very positive outcomes, including further work with Ted Dyrness, culminating in the 1973 book Natural Vegetation of Oregon and Washington, which is still the go-to book on the topic.

Franklin goes on to describe his fourth life, the Conifer Forest Biome work in the International Biological Program (IBP) based at the Andrews Forest. He recounts how the Corvallis team had to battle a University of Washington group to get part of that action. His fifth life was building the Andrews Forest program and facilities. This dates from his first encounter with the forest in 1957 as a student intern through to teaming up with Ted Dyrness to build the program as the experimental forest was threatened with disestablishment in the 1960s, which led to engaging in the IBP. He flags this sixth life as long-term ecological research, which he championed in various ways over many years, culminating in the National Science Foundation establishing the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, which he led at the Andrews LTER site and later the full network of LTER site scales. Mount St. Helens was his seventh life, which he describes in excited terms, but says his engagement was too short. Old growth was his eighth life, which he describes as influencing him since childhood, but its significance and his impacts on it emerged over many decades, as it wove in with IBP, LTER, and some of his other “lives.” Franklin describes his ninth life as New Forestry or ecological forestry – efforts to give forestry a new direction, one better grounded in ecology and ecosystem perspectives. This led to the Gang of Four process to give science input to policy makers, which is just one of a cascade of such activities he’s in the midst of at the time of this talk. He also mentioned getting up into tree tops, which is another adventure just unfolding at the time of this talk – establishment of the canopy crane facility at Wind River Experimental Forest.

Franklin next reviews some of the lessons he has learned over this history, such as patience and persistence. He emphasizes working with other people – individuals and in big teams – and staying flexible. Turning from looking at the past, he shifts to considering the future and how uncertain he is about what the future holds for forestry, the Forest Service, and public lands. He closes with thanks to all who attended and introduces his wife. A few comments from the audience follow.

Franklin begins the lecture by acknowledging people who had major influences on his early career by way of encouragement and example. He then begins recounting his major efforts beginning with subalpine forest ecology, which he found to be an attractive part of the Northwest landscape and little studied. In that period, he learned two lessons: first, if something looks like a good possibility, go for it; second, his objectives were going to evolve, go with it. His second “life” was natural areas, especially Research Natural Areas, and he found that establishment of them could get fraught politically. He describes how this work brought some important opportunities, including engaging young scientists in the program and working closely with Ted Dyrness. His third life was vegetation analysis, which was criticized “not science” and “not truth,” yet working with it led to some very positive outcomes, including further work with Ted Dyrness, culminating in the 1973 book Natural Vegetation of Oregon and Washington, which is still the go-to book on the topic.

Franklin goes on to describe his fourth life, the Conifer Forest Biome work in the International Biological Program (IBP) based at the Andrews Forest. He recounts how the Corvallis team had to battle a University of Washington group to get part of that action. His fifth life was building the Andrews Forest program and facilities. This dates from his first encounter with the forest in 1957 as a student intern through to teaming up with Ted Dyrness to build the program as the experimental forest was threatened with disestablishment in the 1960s, which led to engaging in the IBP. He flags this sixth life as long-term ecological research, which he championed in various ways over many years, culminating in the National Science Foundation establishing the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, which he led at the Andrews LTER site and later the full network of LTER site scales. Mount St. Helens was his seventh life, which he describes in excited terms, but says his engagement was too short. Old growth was his eighth life, which he describes as influencing him since childhood, but its significance and his impacts on it emerged over many decades, as it wove in with IBP, LTER, and some of his other “lives.” Franklin describes his ninth life as New Forestry or ecological forestry – efforts to give forestry a new direction, one better grounded in ecology and ecosystem perspectives. This led to the Gang of Four process to give science input to policy makers, which is just one of a cascade of such activities he’s in the midst of at the time of this talk. He also mentioned getting up into tree tops, which is another adventure just unfolding at the time of this talk – establishment of the canopy crane facility at Wind River Experimental Forest.

Franklin next reviews some of the lessons he has learned over this history, such as patience and persistence. He emphasizes working with other people – individuals and in big teams – and staying flexible. Turning from looking at the past, he shifts to considering the future and how uncertain he is about what the future holds for forestry, the Forest Service, and public lands. He closes with thanks to all who attended and introduces his wife. A few comments from the audience follow.

Creator

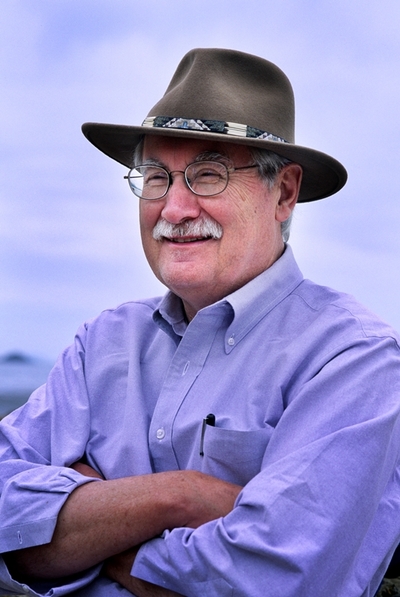

Jerry Franklin

Source

Northwest Forest Plan Oral History Collection (OH 48)

Publisher

Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries

Date

November 22, 1991

Contributor

Fred Swanson

Format

Born Digital Audio

Language

English

Type

Transcribed Audio Recording

Identifier

oh28-franklin-jerry-19911122

Oral History Item Type Metadata

Interviewer

Fred Swanson

Interviewee

Jerry Franklin

Location

Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon

Original Format

Born Digital Audio

Duration

1:17:11

OHMS Object

Interview Format

audio